Maggini Quartet – Haydn String Quartets – CR4627

£9.99 – £15.99

“After reviewing a string of disappointing new Haydn string quartet recordings, this one by the Maggini Quartet comes as a breath of fresh air, even if it is 20 years old. Recommended” Jerry Dubins.

Description

When Haydn wrote his first string quartets in the late 1750s he could hardly have realised that he was about to unleash a revolution in music, leading in a short time to the profound, sophisticated quartets of Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert. But for great musical works one need look no further than Haydn himself. He gave the form a strong, flexible structure and developed the independence of the inner parts, enlivening his scores with rich counterpoint and diverse, inventive textures. This was excellent compost for the cultivation of his fertile, ever-colourful imagination.

His quartets were published mostly in sets of six. But Op. 77, composed in 1799, consists of just two quartets. Perhaps that is why they were not published immediately. Towards the end of March 1802 Haydn’s friend Georg August Griesinger wrote to Breitkopf Härtel: “Artaria will postpone the edition of the two Haydn quartets until such time as he has composed the third, a task to which he will now devote himself”. In the event Artaria did not wait and the two quartets were published that year.

Towards the end of his life Haydn suffered a decline in his ability to concentrate, which distressed him greatly. Op. 103, his last composition, represents a final struggle against failing physical powers. He managed to complete only two movements. A sketch leaf in Haydn’s hand, now in the Yale Music Library, contains material for the quartet. It also includes two short passages, which may have been sketches for the other movements. Fortunately, perhaps, there is not enough material for anyone believing himself to be Haydn re-incarnated to attempt a completion. Attention was drawn to the sketch by M. Jennifer Bloxam in an article published in the Haydn Yearbook in 1983 (vol. XIV). She speculates on the possibility that the Andante grazioso was intended not as a middle movement but as the 1st movement. Its key of B flat matches that of an eleven-bar theme in the character of a rondo finale which appears on the sketch leaf. If, on the other hand, a one-bar fragment for cello in D minor which is also on the sketch leaf were considered the basis for the last movement then one would expect the first movement to be similarly in D minor.

The theory that Op.103 starts with a slow movement runs contrary to the testimony of Haydn’s friend Griesinger, who wrote to Breitkopf & Härtel on 25th January 1804: “he is finished with the Allegro, an Andante and variations, and the Minuet and Trio of his Quartet; only another Allegro is wanting”. But if Haydn completed an Allegro it has never come to light. Seven months later (22nd August 1804) Griesinger was probably nearer the truth when he told Breitkopf that “Haydn has stopped all work because of his health, and a quartet of which he has finished two movements is the child whom he now cares for and to whom he sometimes devotes a quarter of an hour, albeit with difficulty”. A year later (21st August 1805) Haydn had “given up hope of being able to complete the Quartet he has begun”. Finally, in a letter to Breitkopf of 2nd April 1806 Griesinger wrote: “Here, my friend, is Haydn’s swan-song… As an excuse that the Quartet is not complete, Haydn sends you his characteristic visiting card; the words are by Gellert. Haydn doesn’t give up all hope that in a fortunate moment he might be able to add a small rondo. We hope it will happen, but there is not much chance that what Haydn could not finish since 1803 could be added now. But wouldn’t it be fitting to print the visiting card instead of the missing rondo?” And that is exactly what Breitkopf did. The words on the card read “All my strength is gone, I am old and weak” (Hin ist alle meine Kraft, alt und schwach bin ich). Griesinger reported Haydn’s assertion that he had in his head music “far greater than that which has already occurred… Ideas float before him by means of which his Art could be brought much further, but his physical condition no longer permits him their execution”. When Haydn handed over the manuscript of the two finished movements of Op. 103, he said, “It is my last child, but it still looks like me”.

Some commentators have seen his loss of creativity as a consequence of Beethoven’s rising star. It is true that Beethoven was working on his Op. 18 quartets while Haydn was composing his Op. 77 and that both composers had been commissioned by Prince Lobkowitz.

Nevertheless one is bound to ask why his genius should have been intimidated by the challenge of Beethoven but not by Mozart, whom he held in the highest esteem. One important difference is the genuine affection which Mozart and Haydn felt for each other, ensuring that any potential rivalry between them was less significant than the spirit of inspiration.

Albert Christoph Dies described Haydn’s very real difficulties in old age. On August 17th 1806 he “found Haydn unexpectedly weak. His formerly sparkling eyes were dull, his complexion very yellow; he complained besides of headache, deafness, forgetfulness and various ills. With difficulty I concealed the degree to which I felt sorry for him and sought to bring up pleasant topics of conversation… At the question “How long is it since you have touched your pianoforte?” he sat down to it, began slowly to improvise, struck some wrong notes, then looked at me, corrected the false notes, and struck some new ones in the correcting. “Ach!” he said after a minute (the playing lasted no longer), “You hear for yourself, it is no good anymore! Eight years ago it was different, but The Seasons has brought this evil on me. I never should have written it! I overworked myself at it!” A year later matters were even worse, when he sat down from time to time at his English pianoforte to improvise, dizziness overcame him after a few minutes. “I never would have believed,” he said on September 3, 1807, “that a man could collapse so completely as I feel I have now. My memory is gone, I sometimes still have good ideas at the clavier, but I could weep at my inability even to repeat and write them down”.

However, an earlier quotation from Dies (March 15th 1806) puts the matter in a brighter perspective, “Woven into Haydn’s character is a genial, witty, teasing strain, but with it always the innocence of a child… He seems, for example, to find pleasure in painting his state of health worse than it really is. On such occasions I usually make answer that in his appearance not a trace of indisposition is to be seen. The brightness which then spreads over his face confirms that one has guessed the truth, although he pictured the opposite”.

Op. 77 No. 1 in G

The quartet opens with a bouncy rhythm betraying not old age or weariness but youthful joie de vivre so infectious is the theme that the second subject threatens to claim it, too. Haydn breaks free, however, creating a variety of musical material dominated by triplets. The development explores this rich territory, with a false recapitulation quite early on to catch the unwary. One fine idea, a beautiful new harmonisation of the first subject, is held in reserve for the coda.

The Adagio opens in noble unison. In this movement dignity and solemnity are contrasted and miraculously enhanced with ornamentation of great delicacy, even more elaborately worked later in the movement. There are fine harmonisations of the original unison theme in the recapitulation and in the poignant coda.

A Minuet marked Presto is a Scherzo in all but name, and the 1st violin twists and teases, leaping with Cossack agility onto the second beat of the bar. This so excites the lower voices that the cello insist on a repeat, while the rush of adrenalin inspires the 2nd violin and viola to some demented scale practice in thirds. The Trio section is stern, its severity scarcely mitigated by the contrasting soft dynamics.

The last movement starts (Finale) with deceptive simplicity – deceptive because the theme contains the seeds of complicated counterpoint to come. Heard at first in unison it proclaims cheerful joviality, but it is no surprise to find Haydn subsequently harmonising it in many different ways. Equally striking is his ability to work the pithy material into long musical lines. The movement features soloistic writing for the 1st violin, but the musical interest and vitality of the inner parts are not sacrificed. Spirited and light-hearted, the music is at the same time profound, with the viola’s trenchant E flat in the final bars reminding us that the comdie humaine, in the eyes of the 67-year-old Haydn, is many-faceted.

Op. 77 No. 2 in F

The confident forte of the opening is almost immediately contradicted by a hushed piano, presenting the extrovert and the introvert within the same phrase. The transitional section seeks out harmonies of poignant intensity, leaning on them repeatedly, before arriving safely in the dominant for the second subject. Here a new melody is heard, but, blissfully unaware, the 2nd violin is still playing the old tune. The gravitational pull of the 1st subject finally entices the 1st violin to acknowledge that the subjects are in fact linked. The development is remarkable for its modulation and richly chromatic harmony, sometimes a little too close for comfort to the Representation of Chaos in The Creation.

The Menuet is placed second. In the Clementi edition, printed in London at about the same time as the first Viennese edition, the Presto marking is modified to Presto ma non troppo. H.C. Robbins Landon claims that it may have been an alteration made by Haydn himself. In this movement a loose cannon persistently fires off a two-note motif to ricochet within a three-in-a-bar structure. It requires a Trio in five flats, legato throughout, to restore tranquillity.

A set of variations follows, whose theme is given out initially in sparse two-part writing. How sonorous are the four parts when the complete quartet is finally brought into play, but Haydn has cunningly enhanced the effect by keeping all the instruments in their lowest register. An interlude, giving opportunities for modulation, connects each variation.

A call to attention introduces the Finale. There follows music of breath-taking energy, rejoicing in polonaise-like rhythms. Finely turned in detail, virtuosic, majestic in its sweep, the movement makes a fitting conclusion to the 67 surviving complete string quartets by Haydn, a genre into which, from its pre-classical embryonic state, he breathed the spirit of his genius to reach a peak of perfection.

Op. 103 in B flat/D minor

Haydn’s last composition, unfinished as it stands, shows no diminution of his powers. The mood is one of affecting serenity, a peace that registers the experience of a long, intensive creative life. The Andante grazioso is in ternary form, its smooth opening melody buoyed up by luminous counterpoint in the lower voices. The middle section, more earthy, brings a flurry of triplets from the 1st violin, in which all the voices eventually participate. The return makes no new additions to the opening statement, saving the element of surprise for the pungent chromaticisms introduced in the brief coda.

Chromatic intensity is maintained throughout the D minor Menuet, whose restless harmonies create a sense of disturbing unease. The disproportionate length of the second section, more than four times that of the first, increases the impression of imbalance. The Trio, switching to the major, offers gentle relief, but we are constantly reminded, through the irregularity of the phrase structure, that in Haydn there is no place for complacency, and that as long as he could still compose, the fire burned within him.

© Michael Freyhan 1996

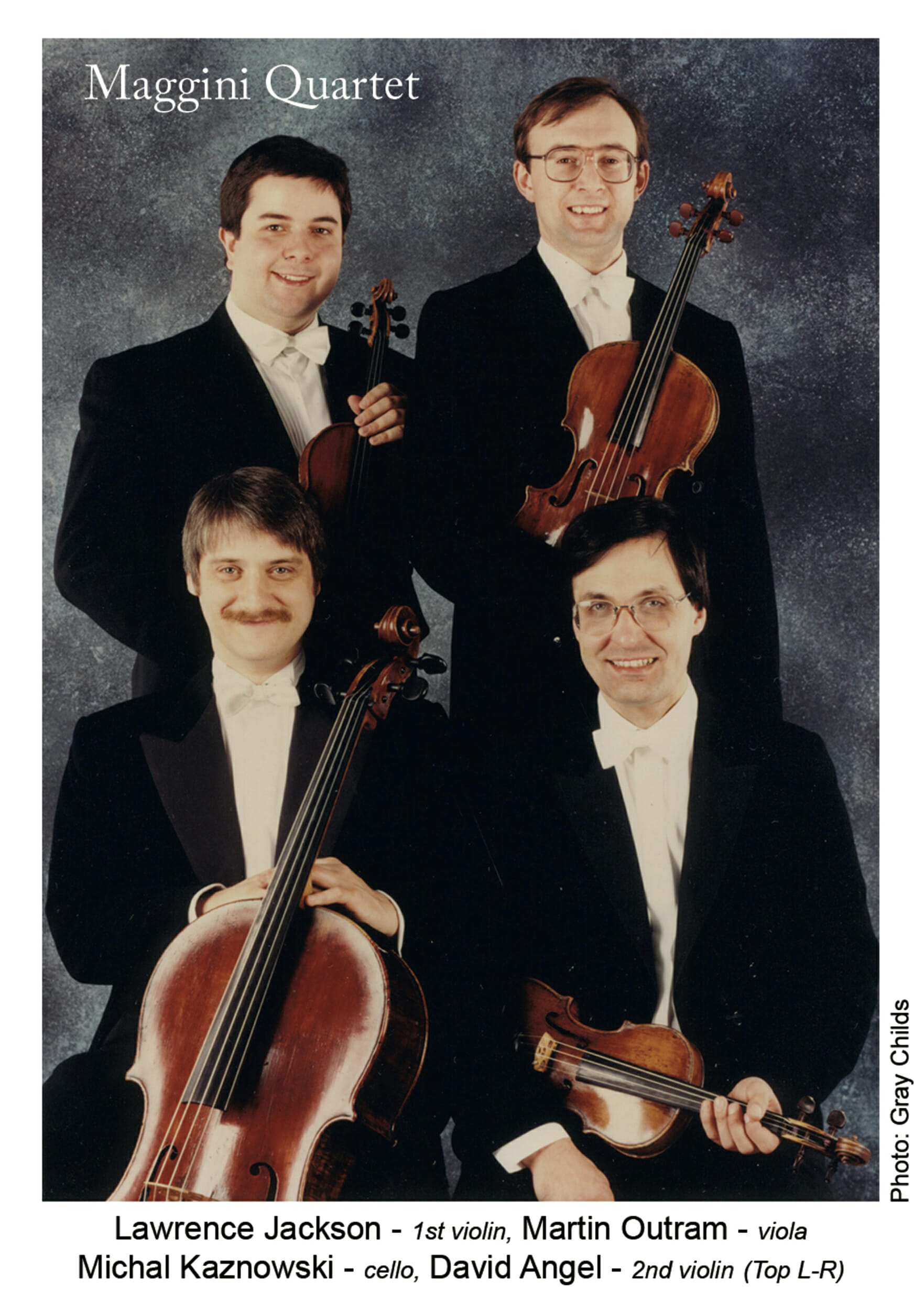

Four musicians whose delight in their work is irresistible, the Maggini Quartet has quickly established itself since its inception in 1988 as a highly acclaimed international quartet appearing at festivals and major halls throughout the UK, Europe, the USA, Japan and Korea.

Their previous recordings cover a wide range of repertoire, including quartets by Haydn, Schubert (Death and the Maiden) Szymanowski and Bacewicz which all received exceptional reviews. Forthcoming releases include works by Bridge, Moeran, Elgar and Britten.

The Maggini Quartet has commissioned a number of works, including Robert Simpson’s Cello Quintet, premiered in 1996 at Cheltenham International Festival. 1996 also saw the first performance of Olivia’ by Roxanna Panufnik at Brunel University, London. Among other highly successful commissions are quartets by Eleanor Alberga and David Gow.

The Quartet plays regularly at many leading UK chamber music venues and on BBC Radio 3. Its members are also experienced in coaching chamber music at the Birmingham Conservatoire, and run several other courses each year. They hold residencies at Brunel University, Christ Church College Canterbury and South East Arts (1994/6).

The Quartet’s name derives from the famous 16th century Brescian violin maker Giovanni Paulo Maggini, an example of whose work is played by David Angel. Laurence Jackson plays on a Flemish violin circa 1720, maker unknown, Martin Outram on an 18th century viola, maker unknown, and Michal Kaznowski on a cello by Jacobus Philippus Cordanus, made in Genoa in 1776.

The Maggini Quartet wishes to express its grateful thanks to Professor George Hadjinikos for the inspirational help which he has given over many years.

The recording of this CD has been made possible by Lincoln National’s support of Brunel University Arts Centre, winners under the National Heritage Pairing Scheme. Lincoln National also sponsored the Maggini String Quartet’s 1995-1996 residency at Brunel University.

This article originally appeared in Issue 40:1 (Sept/Oct 2016) of Fanfare Magazine.

Previous encounters with Britain’s Maggini Quartet have been generally positive, though I can’t say the same for the repertoire in which the encounters took place. The ensemble has dedicated itself almost exclusively to 20th-century English composers, gaining special notice for a series of recordings of string quartets by Peter Maxwell Davies, commissioned by Naxos.

It would be an encouraging sign—for me, at least—if, with this release of Haydn quartets, the Maggini had finally decided to turn its attention to the Classical string quartet literature, because everything I’ve heard by this ensemble has been top-notch in terms of performance, even if I haven’t cared much for the music being performed. Alas, however, the recording at hand does not necessarily portend the Maggini’s future direction; rather, it’s a glance in the rearview mirror at the ensemble’s past, for these Haydn quartets were recorded in 1996, when the young players were Artists in Residence at West London’s Brunel University.

It’s a pity, really, that the Maggini hasn’t recorded more of the mainstream repertoire because the performances on the present album are among some of the best Haydn I’ve heard—buoyant, perfectly timed, and deadpan-British in their tongue-in-cheek humor. I note on the Maggini’s official web site that the ensemble did appear in Bergen in January of this year in a program of Haydn, Brahms, and Malcolm Arnold, so perhaps the players are once again taking up some of the great string quartet literature of the past.

Meanwhile, since being founding in 1988, there has been only one turnover in the Maggini’s personnel, but it was the most critical one of all, the chair that usually exerts the greatest influence over the personality and characteristic sound of a string quartet. Lawrence Jackson, who played first violin on the present Haydn recording, was replaced by Julian Leaper, who now currently occupies the position.

The three Haydn quartets on this disc are the composer’s final essays in the medium. The two op. 77 works, familiarly referred to as the “Lobkowitz” Quartets for Prince Lobkowitz who commissioned them, are believed to have been only the first installments in a set of six quartets the Prince had requested. Whether the others were lost, destroyed by Haydn, or never written in the first place remains a bit of a mystery. One of the more interesting theories, though, is that in 1799—the autograph date of the two op. 77 Quartets—having heard one or more of the op. 18 Quartets by his one-time unmanageable student, Beethoven, Haydn knew that his day was done, that the music world had moved on and it was time for him to defer to a new order.

That’s a fine theory, except for one big hole in it: Four years later, in 1803, Haydn decided he wasn’t quite done for, not just yet anyway, for he embarked on a final quartet, which was published as op. 103. But this last quartet poses unanswered questions of its own. Haydn completed only two movements, an Andante and a Menuetto, presumed to be the two inner movements of a projected four-movement work. Was this quartet to have been a continuation of the Lobkowitz commission, a third installment in the op. 77 group? And if so, why didn’t Haydn complete it?

We know that by 1803 the composer was already in quite poor health and no longer able to muster the physical strength or mental concentration required to compose, so maybe the simple answer is that he was too ill to carry on. Despite futile attempts at completing the quartet as late as 1805, the two movements he did manage to finish may have been the last music he wrote. The Andante in particular has a certain nostalgic, valedictory character to it.

After reviewing a string of disappointing new Haydn string quartet recordings, this one by the Maggini Quartet comes as a breath of fresh air, even if it is 20 years old. Recommended. Jerry Dubins.